Mom Was an Atheist who Taught me to Believe

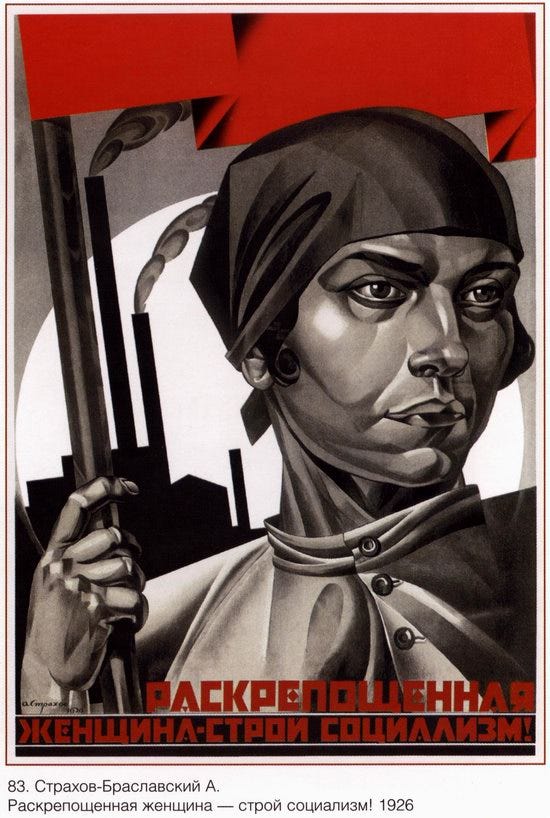

She joined the Communist religion in the l930's and remained a believer all her life.

My mother always hated religion. "Hocus-pocus," she called it. Even the mention of God made her sneer. She grew up in an era rife with anti-Semitism, so she had no sympathy for Christians, especially Catholics, who taught that Jews killed Christ. But she had no love for Judaism either, seeing the orthodox of her own religion as a bunch of fanatics with long beards and joyless lives, and reform Jews as bourgeois and materialistic. Instead she joined the Communist religion in the l930's and remained more or less a believer all her life.

Mom brought me up to be a devout atheist, even though she had regrets about depriving me of Jewish culture. For a while she’d sent me to Sunday school in an attempt to force some Jewishness down my throat, but I hated it. The Bible stories were boring and the teacher got on my nerves. I sat in the back and fidgeted until one day the teacher asked if there was anyone in class who didn’t believe in God. I proudly raised my hand, sealing my fate as a pariah. Mom pretended to be dismayed, but from then on laughingly bragged that I’d been thrown out of Sunday school because I had the chutzpah to admit I didn’t believe in God.

My parents didn’t exactly flaunt their atheism, however. They were acutely aware of being Jews in a country where antisemitism was still common, and I was kept out of school on the Jewish holidays even though we didn’t celebrate them. When I asked why, Mom said it would look bad to the goyim if I went to school on Rosh Hashanah or Yom Kippur. We usually left town on the high holy days, escaping to a Russian resort on a lake not far from New York City. We’d listen to groups of Russians singing mournful songs and guzzling vodka, while we rebelliously picnicked on ham sandwiches.

The only Jewish holiday we did celebrate was one of my favorite days of the year--Passover. We’d go to a Seder at one of my parents’ Jewish lefty friends. Someone would read a couple of pages of the Haggadah while we kids surreptitiously guzzled Manichewitz, until the grownups gave in to our pleas of let’s eat. The Haggadah was quickly discarded in favor of the meal. But something about the spirit of those Passovers stuck with me, and as an adult I try to get to a Seder every year no matter.

When mom, in her mid-eighties, came up to visit me in Woodstock, New York where I was living at the time, I took her to a Yom Kippur service at my synagogue, the Woodstock Jewish Congregation. Held under an enormous tent, open to all, it resembled a Jewish tent revival. Our services rang with real spirit, not the phony piousness she’d experienced in her youth. A lifelong fan of folk music, if not of Judaism, she immediately took to our rabbi, Jonathan Kligler, a former folk singer whose services resembled a hootenanny.

She endured a discussion of the "Book of Job," and later whispered to me, wrinkling up her nose, “He talked so much about God. You don't believe in all that God stuff, do you?” I still wasn't sure there was a God, but if I did decide to believe, I sure wasn't going to admit it to my mom. Rabbi Jonathan told us we didn’t have to worry about whether or not we believed in God to lead a Jewish life. God wouldn’t care either way. The essence of Jewishness was doing mitzvahs, or good deeds. I was surprised that mom approved of my joining a synagogue at all, but our congregation was so unlike anything she'd ever experienced that it won her over. I suggested she attend services in Florida. She shrugged her shoulders, "I would if they were led by your rabbi."

My mom only got to attend services a couple of times before her health prevented her from coming up north to see me. I traveled to Florida regularly to deal with one health crisis after another. She developed dementia and could no longer keep up with her friends. An intensely social and boundlessly energetic person, she became so depressed she refused to get out of bed.

During one phone conversation she said, "There has to be a change."

"You mean to an assisted living facility, mom."

"Oh no," she said, "Not that kind of change," but didn't explain what she meant. Then, during our daily phone calls, she started asking frantically when I was coming to visit. I gave her the date many times, but she would repeat the question plaintively, over and over, day after day, week after week.

I didn't understand the urgency. Her condition seemed to be stable and I'd finally found Kathy, a wonderful aide who mom adored. When I finally did arrive, she threw her arms around me and wouldn't let go, saying, "I love you so much." I started crying. She’d never been a demonstrative woman.

From that moment she started, or finished, dying. Her kidneys simply failed, for no particular reason. I’m convinced she had decided to die and her body was shutting down. We had discussed her profound wish to avoid heroic life-saving measures in such a situation, so I refused dialysis when the doctor offered it. Josie, a large, cushiony, comforting Jamaican hospice nurse stayed by her side much of the time.

I called a rent-a-rabbi someone recommended, feeling that a spiritual advisor should be on hand to comfort the dying, even if she was an atheist. The rabbi, who somehow had missed his vocation as a stand-up-comic, showed no inclination to comfort my mother, who in any case was past comforting, but he did have me laughing out loud at joke after joke, a mitzvah that lightened the weight of my grief for the moment.

Mom got worse rapidly, soon losing all lucidity. One day she looked right through me and said in a sing-songy, high-pitched voice I didn't recognize, "Who are you?" It felt as if she’d physically shoved me away. Much as I wanted to be there for her when she died, I found I simply didn't have the strength to watch her dying, although I knew that if our places were reversed, she wouldn't have left my side for a moment. I was desperate to return home--to my own nest where, like a wounded animal, I could grieve and lick my wounds. Riven with guilt and self-reproach, not knowing how long she would live or if my presence still mattered to her or not, my husband and I flew home, intending to return in a week or so.

That "I love you so much," was goodbye. By the next morning she was gone. I had to leave her so she could leave me.

If, as many Buddhists assert, spirituality means experiencing each moment to the fullest, mom could have been a Zen master. Unlike me—a self-absorbed writer who analyzes every moment—mom actually lived in the moment. I'd seen her transfixed by a bird's nest under the eaves of my house, studying it for hours every day, waiting for the baby birds to emerge, and when they did, she peppered me with a million bird questions as if I was an ornithologist. She became rapturous over an art exhibit, a ballet, a concert, an evening watching the moon rise over the ocean. Even a week before she died, when she couldn't walk and could barely speak, she looked blissfully content when I wheeled her out to the pool so she could visit with a group of beloved old friends. Just their chattering presence and the warmth of the sun seemed to fill her with peace and joy.

My mom was no saint, however. She loved to gossip and regularly committed the sin of leshon hara. She despised boring people, preferring witty folks with an edge. She once slyly admitted to me that she agreed with Alice Roosevelt Longworth who quipped, “If you don’t have anything good to say about anybody, come sit by me.

She was a great friend, but a lousy mother. Hypercritical and overbearing, she constantly harassed me about my weight and failure to become the stylish, charming daughter she could show off to her friends. Unhappily married to my dour, uncommunicative father, and stuck in an era with no career opportunities for women, she wound up taking her frustrations out on me. She became a schoolteacher although she once told me her dream was to be a theater producer. When she retired from teaching, all she wanted was to hang out with friends, travel the world, and indulge her endless curiosity about life. She did not want to be caregiver for my father who had Parkinson’s.

After my father died, she and I became great friends and I finally got to appreciate her zest for life. We went to plays and concerts and I even took her snorkeling in the Keys when she was in her seventies. Despite her failings at nurturing, I knew she was devoted to me, helping me out financially throughout my life and always encouraging my achievements.

Although she scoffed at the notion of God, and knew nothing about Judaism, she brought me up to be a good Jew. She was my role model when it came to helping others, regularly performing numerous mitzvahs herself. She fervently believed in tikkun olam, repairing the world, which Jews view as a spiritual duty. Most of all she taught me that spirituality is about what you do, not what you believe.

I read somewhere that the last thing a parent teaches you is how to die. My mom was never afraid of death, even as it stared her in the face. She faced death with a grace and dignity I can only hope to emulate when my times comes. Josie told me she died "a lovely death." Right before she died the color returned to her cheeks, and she tried to get out of bed, as if reaching for someone who was there to greet her. Josie claims to have actually seen my mother wave at a spirit, a "white lady in petticoats and an old-fashioned dress," who appeared in the room.

The Kabbalah teaches that there is an afterlife. Call me a flake, but I believe that figure was my mother's mother.

I still miss my mom. Despite her failings, no one else ever really cared about me as much as she did. I comfort myself with the knowledge that, whether there is or isn't a God, I'll see her again someday. Mom, who always managed to push her way to the front of the line, will surely turn heaven and earth to be there when it's my turn to pass from this world. An atheist to the end, she taught me it was possible to believe.

This entire essay is a paean that captures the human condition pretty effectively.

Very nice piece, Erica. Question: was the Russian resort that your mother took you to called Rova Farm? My parents went there once a year, after attending an annual conference in Philadelphia.